As Cambodians wake and shake their dreams from their slumbering limbs, they face a real working day that is likely to revolve around rice. According to a recent report by the New York Times, 80 per cent of the population work on the paddies. Which explains why Da, a Cambodian now transplanted to the urban fringes of London, says that Chicken Rice Soup — or borbo sach moan — runs in her veins…

Cambodia dreams of rice. When night falls over gold-peak temples, it stalks the nightmares of this green Buddhist kingdom, bordered by Thailand to the north-west, Laos to the north-east, Vietnam to the east and south, and the turquoise Gulf to the south-west.

Cambodia dreams of rice. When night falls over gold-peak temples, it stalks the nightmares of this green Buddhist kingdom, bordered by Thailand to the north-west, Laos to the north-east, Vietnam to the east and south, and the turquoise Gulf to the south-west.

"If we have dikes, we will have water; if we have water, we will have rice; if we have rice, we can have absolutely everything,” shout the night-terrors, echoing the cries of the Khmer Rouge who seized the country in 1975. In Pol Pot’s ‘four year plan’ for the country, the first eighty-five pages are devoted almost entirely to one topic: goals for rice production. So it was that cities and towns were emptied, and almost the entire population – doctors, lawyers, bricklayers and waiters – were sent to work in the rice fields.

Children under the age of fifteen grew vegetables or raised poultry. Everyone, however, worked at least a ten hour day and by the regime’s fall just four years later, more than 20% of the population had died in pursuit of the rice dream, some from exhaustion, others from starvation, disease or execution.

Today, as the light begins to come up over the banks of the great Mekong River, the kingdom’s lifeblood, rice also dominates the country’s dreams for the future.

In 1978, when Vietnamese troops invaded Cambodia, the ensuing turmoil completely disrupted the nation's agricultural production. Cambodia’s rice exports have, ever since, been dwarfed by those of neighbouring Thailand and Vietnam.

That may be about to change, because in 2010, the government launched an ambitious new plan to boost the country’s economy. “The policy aims to ensure that we grab the rare opportunity to develop Cambodia in the post global financial and economic cataclysm,” said Prime Minister Samdech Hun Sen. It’s name? The Rice Policy. If Cambodia’s rice industry were to reach its full potential, it’s estimated, it could produce 300 million tonnes of milled rice annually, boosting the economy by $600 million. That’s a big dream.

But back to today. As Cambodians wake and shake these dreams from their slumbering limbs, they face a real working day that, too, is likely to revolve around rice. According to a recent report by the New York Times, 80 per cent of the population work on the paddies. Which explains why Da, a Cambodian now transplanted to the urban fringes of London, says that Chicken Rice Soup — or borbo sach moan — runs in her veins.

But back to today. As Cambodians wake and shake these dreams from their slumbering limbs, they face a real working day that, too, is likely to revolve around rice. According to a recent report by the New York Times, 80 per cent of the population work on the paddies. Which explains why Da, a Cambodian now transplanted to the urban fringes of London, says that Chicken Rice Soup — or borbo sach moan — runs in her veins.

“I could cook this at five years old,” she says, casting a critical eye over my rice-rinsing as we recreate the soup in my kitchen. “Every Khmer boy or girl knows the recipe. Every family feeds it to people who are feeling unwell.”

“We eat together in my country,” explains Da. “Cambodians are very family orientated. Whether you are a great-granny or a baby, you get together for meals.”

As she talks, I’m reminded of the traditions behind the Jewish chicken soup we cooked last month: of healing; of recipes as vessels for community history; of bringing and binding family together, even in the most difficult situations. Even the base ingredients are familiar: a boiled chicken, its broth and rice. Yet all the while, I am shredding exotic oyster mushrooms and measuring out fish sauce, and I am reminded that, from the confines of my small suburban kitchen, I have travelled half way across the world again.

Other guests dribble in and stand to admire Da’s matriarchal authority over the cooking process. Hannah has been to Cambodia, “But I never had food like this,” she says. “You won’t find this recipe in a restaurant,” says Da. “It’s what people cook at home, or eat late at night.”

Other guests dribble in and stand to admire Da’s matriarchal authority over the cooking process. Hannah has been to Cambodia, “But I never had food like this,” she says. “You won’t find this recipe in a restaurant,” says Da. “It’s what people cook at home, or eat late at night.”

“It’s different cooking it here,” she admits. For one: “At home, people would cook it over a fire, not on a silly hob.” And then there’s the shopping: “At home, everything would come fresh, fresh, fresh, from the market. You go to a market and buy a chicken – it’s alive in front of you. They have to kill it for you.”

Now, she goes far and wide to find Asian supermarkets and, less exotically, to Asda to buy meat because she thinks their organic range is best. I can’t help thinking it must affect the alchemy of the dish somehow, this sanitization of the shopping ritual, from sensual to soulless.

Da agrees it does make the final dish taste slightly different but she has one secret ingredient up her sleeve, spirited from back home and contained in a tiny pot that emerges from the bottom of her handbag. She unscrews the lid and wafts it, ceremonially, under my nose. It’s pepper, but not as I know it. Spicy, but softly fragrant too. It is Kampot pepper, “the world’s best,” says Da, in tones that brook no argument.

The contents of this tiny pot come all the way from a region of Cambodia that is nestled between mountains and the sea, creating a perfect micro-climate for growing pepper: rich soil, lots of rain and blistering sun. Peppercorns have been produced there since the 13th century, but under French colonial rule its fame spread across Europe. Kampot pepper is the first Cambodian product to receive a Protected Geographical Indication (the certification that protects regional products like Champagne and Parmesan).

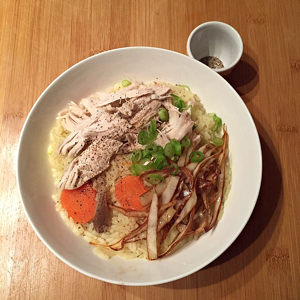

Da sprinkles this precious taste of home over the bowls and we are ready to eat.

The Guest List:

Me

Tom—the husband

Da—the Cambodian cooking queen

Mal—my friend, her neighbour, through whom we were introduced

Hannah—a world-adventuring journalist

Paul—my father

The Verdict:

Paul having just had a hip operation, I was half expecting a miracle whereby he tasted the soup, threw down his crutches and did a celebratory jig on the table-top.

It didn’t quite happen like that. But there was something else, something perhaps more important.

We could not have been much further from the picture of a conventional Cambodian family, cooking and eating it for conventional reasons in a conventional setting. Nonetheless, the soup had found a way, 6,000 miles from its homeland, to exercise its traditional magic.

In a city where neighbours are too busy to form a community and families are too frantic to sit down together to eat, it had brought together, around the table, not only different generations but also Da and me, two women living a stone’s throw from one another who otherwise would have been living in entirely separate worlds.

Oh, and the soup was utterly delicious too.

Da’s Cambodian Chicken Soup

Ingredients

1 whole chicken

12 tablespoons jasmine rice

3 tablespoons vegetable oil

9 chopped cloves of garlic

10 baby spring onions

3 chopped carrots

9 oyster mushrooms

3 teaspoons palm sugar

3 teaspoons salt

Fish sauce

Cooking method

- Put the rice in a pan and rinse it several times, till the water runs clear. Then soak it for several hours (you can leave it all day)

- Put the chicken in a large pot and submerge it in water. Add a teaspoon or so of salt and sugar (equal measures) and simmer for about two hours. DO NOT drain the water away - it will be used for the soup!

- Remove the chicken from the water and shred it, discarding the bones.

- Place a pan on the hob and, once hot, add oil. When the oil is hot, add finely chopped garlic and three-quarters of the spring onion and fry until golden brown.

- Add the drained rice, stirring occasionally till it is glossy and golden. Then pour in the water from your chicken, bring to the boil then simmer.

- Once all the water has been absorbed from the top, add more (plain) water generously.

- When the rice is soft and puffed, add the chopped carrot & leave to cook for another 5–10 minutes.

- Now add the oyster mushrooms—having torn them into strips by hand—and stir into the soup.

- Leave to cook for another 5 minutes.

- Remove pan from the heat and pour the soup into serving bowls. Top with shredded chicken and sprinkle a pinch of ground black pepper into each bowl of soup.

Serve with optional toppings of finely chopped spring onion and fish sauce.

Optional side dish:

Garlic

Chinese cabbage

- Discard the outer leaves of a cabbage, then cut the inside into thin strips. Finely chop 5 cloves of garlic.

- Heat a pan, then add vegetable oil and, once hot again, add the garlic.

- Cook for a few minutes, stirring occasionally, then add the cabbage.

- Once crispy, remove from the pan and serve to one side of the soup.

Da runs cooking courses and does private catering. Everyone should get to know her and her cooking, I promise that both will improve your life immeasurably: http://dacambodiancooking.com/

Here is the recipe as a PDF.

Join us next month to test a new chicken soup. Get in touch with suggestions of all sorts via Twitter: @hattiegarlick